No Strings--for Now : Grant Gives Puppeteer Less Tangled Future

- Share via

Two years ago, Bruce Schwartz stopped being a puppeteer.

Into storage went Marie Antoinette, Chrysalis and Dame Eleanor--and all the exquisite hand-sculpted, hand-designed figures he’d created and performed with for a decade.

Schwartz gave up a stunning 2,000-square-foot downtown Los Angeles loft, which had served as both a work and living space. He dropped his middle initial “D.” And he took a 9-to-5 job as a sales person at a local gallery.

Last month, he was named the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a $215,000 grant that will be paid over the next five years. It is a no-strings-attached award, and Schwartz, who was nominated anonymously and says he was “shocked” to be chosen, isn’t so sure he intends to resume his puppetry.

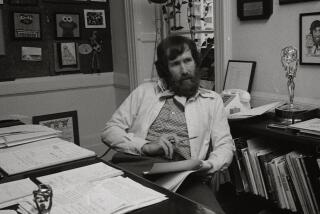

At 32, Bruce Schwartz looks happy, sounds happy. Although his words are serious and reflective, there’s little of the somber intensity that was visible in an interview five years ago.

“I’d toured for years at a stretch,” he recalled. “I was confronted with either staying the same or doing something new. I mean, I could’ve taken my one-man show (“Personal Effects”) around the world indefinitely; there are lots of little venues in Europe.

“The alternative was staying here and coming up with new material. But puppet theater is extremely labor-intensive. And the direction my work was taking involved using more people, other disciplines, a larger scale.

“I needed more time, and that translates into money. As soon as I finished one project, there was no time to recharge, relax--I had to start the next one. I constantly had to work. At the time, the only way I saw to rest was to dismantle my career.”

There’s no hint of pain in the decision--or any sense of regret or failure. “I wasn’t powerless,” he said firmly. “I was empowered by the fact that I could stop, proud that I could walk away from it--because it had been so integral to my entire persona: I was Bruce D. Schwartz, puppeteer; I’d been that since I was a little boy.”

“So to let that go--because it was no longer good for me--felt like a reassertion of my integrity. Not that I would characterize my work as a crutch. But I found I didn’t need it to survive.”

Which isn’t to say that he doesn’t miss performing--occasionally.

“I haven’t said I’ll never perform again--but on the other hand, I haven’t felt it was time yet to begin performing,” he said. “There’s something very unique about creating a puppet. I miss the absorption, the direction, being totally focused on that figure.”

And applause?

“Those responses had taken on a bitter irony the last years when I was working,” he noted, “because it was essentially so hollow. It was like, ‘Thank you very much for feeling that way about my work--but I wish you would understand what this is doing to me, how hard this is.’

“Since the article about the award came out in The Times I’ve gotten lots of letters from people who’ve seen the shows, saying, ‘You owe it to the world. . . .’ ”

Schwartz frowned. “I do feel an obligation to my potential; we all do. When you’ve given that up, you’ve given up.

“But I think that’s also got to be negotiated. I don’t think you have to make yourself miserable because you have a gift. I mean, being good at something is not reason enough to do it. You have to be able to do it and grow--not kill yourself.”

Wouldn’t the MacArthur money fix that?

“It does throw a new factor into the quotient,” he said. “I’ve thought, if this had only happened two years ago, it would’ve seemed like manna from heaven.

“But having gotten the MacArthur Fellowship then would’ve circumvented my being able to make the choices I’ve made--which were very important choices. It’s like the Good Witch tells Dorothy at the end of ‘The Wizard of Oz’: ‘You had the power to go home all along.’ ‘Why didn’t you tell me, before I had to go through all this?’ ‘Because you wouldn’t have believed me.’ ”

Part of the lesson seems to include liberation from being regarded as a “special person.”

“I don’t think I’d phrase it quite that way,” Schwartz said gently. “I am who I am, and part of that is an artist. You don’t leave that at the door; it’s something that you are. So it’s not like I’ve severed a limb.

“But I’ve also gained independence from it: learning you don’t need those external kudos to feel like a worthwhile person, that you have an identity beyond what is given you in the eyes of your audience. What I’ve found through my interest in Japanese culture is that everybody is valued, everybody’s work is honored. Whatever you do makes you extraordinary.”

One aspect of his life-change has been an increased politicization.

“(Before), I didn’t have a lot of time to give to political work--or any kind of work--because I was either traveling around the world or beating a deadline. Which meant it didn’t matter whether or not they bombed Grenada, because I had to be ready with this puppet by Tuesday.”

“It’s not just artists; we all become self-absorbed. If people didn’t have that level of denial, we’d all go crazy in 24 hours. If you really thought about the suffering going on in the world, how could you possibly sit down to dinner?”

Schwartz became active in the 1986 “No on 64” (Larouche initiative to quarantine AIDS carriers) campaign. “It gave me the means to express a feeling I’d had for a long time: that the AIDS epidemic was encroaching on my rarefied world of art--and that it was something that couldn’t be ignored.”

He doesn’t, however, believe in mixing art with activism. “I’d rather storm the Bastille than do a play about it,” he shrugged. “I feel like AIDS plays and AIDS novels only serve to siphon off people’s grief and anger--so that nothing really happens on the street. I think that nonviolent civil disobedience is a more effective way of combating the government’s lack of action.”

Schwartz has also discovered the joys of the regular job. “This has been my first job ever,” he said proudly. “It’s probably something most artists learn to negotiate very early in their lives: They have their ‘straight’ job, then they do their art--and it’s separate.

“But to me it’s been a revelation. Maybe this is the way to proceed, to keep the pressure off: that your sole source of income is not dependent on your production as an artist.”

Which means, at least, the contemplation of the return of Bruce Schwartz, puppeteer? He allowed a small smile. “Maybe.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.