Lyme Disease Vaccine Developed : Medicine: Genetically engineered inoculate could be tested in humans in three years. It protects mice from infection and kills bacteria in ticks that carry it.

- Share via

Yale University researchers have developed a unique vaccine for Lyme disease, a disabling infection that strikes at least 9,000 Americans each year. The vaccine could be tested in humans in as little as three years.

The disease is caused by a bacterium that is transmitted from wild animals to humans by ticks. The researchers report today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that the genetically engineered vaccine not only protects mice from infection when they are bitten by bacteria-infested ticks, but that it also kills bacteria in the ticks that bite the mice, thereby disrupting further transmission of the disease.

Destruction of the bacteria in their host by a vaccine has never been observed before. It suggests not only protection for humans and other animals bitten by the mite, but also disruption of transmission of the disease through its animal hosts, said Dr. Erol Fikrig, an infectious disease specialist at Yale, who was co-director of the study with Dr. Richard A. Flavell, a Yale immunologist.

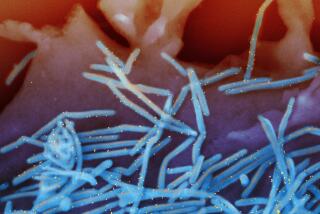

Lyme disease is named after the town of Old Lyme, Conn., where it was first recognized in 1975. It is caused by an unusual spiral-shaped bacterium, called a spirochete, that is similar to the bacterium that causes syphilis. Fikrig said his apparent success in devising the Lyme vaccine could also lead to the development of a syphilis vaccine.

The number of cases of Lyme disease reported annually has more than tripled since 1985, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, with 9,344 cases reported in 1991. Most were in the Northeast, but 323 were in California. Some experts believe that as many as 90% of cases are not reported to the CDC because doctors fail to recognize the disease.

The disease begins with a characteristic bull’s-eye rash that appears within a few days after a tick bite. The infection can be easily controlled with antibiotics such as penicillin and tetracycline. But if it is left untreated, it can cause facial paralysis, vision and heart problems and a severe form of arthritis.

The Yale team has had to overcome a number of problems in developing the vaccine. Foremost was finding an animal model. Although mice in the wild harbor the spirochete, they do not develop symptoms of the disease. Yale veterinarian Stephen Barthold spent more than a year exposing various strains of mice to the spirochete before finding one susceptible strain.

Meanwhile, Fikrig and his colleagues isolated a large protein, called OspA, from the cell wall of the spirochete and used genetic engineering to produce large quantities of it. When they vaccinated mice with OspA, it produced antibodies that protected the mice against laboratory injection of the spirochete, a feat they achieved 18 months ago.

But critics charged that their results would not be convincing until they showed that the vaccine protected the mice against infection carried by the ticks. When the ticks bite, they inject into the victim’s bloodstream a chemical that causes suppression of the victim’s immune system. Experts feared that this immunosuppression might negate the effects of the vaccine.

The team reports today that mice bitten by ticks were also protected against infection. Furthermore, when the researchers examined the ticks 10 days after they had bitten the mice, they found no trace of the spirochetes--a finding Fikrig said is unique.

He said the discovery opens the possibility that transmission of the disease in nature could be disrupted by vaccinating the wild mice that harbor the ticks. Such an effort would be modeled after studies in progress to interfere with rabies transmission in the wild.

In that experiment, which has been successful in Europe and the United States, bait containing the vaccine is scattered throughout target areas. Wild animals eat the bait and become immune to rabies, thereby stemming its spread.