Weber Finds Patience Wins Race at Dorsey

- Share via

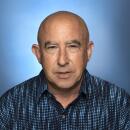

When Nathaniel Weber started walking around Los Angeles Dorsey High’s campus last fall, some of his fellow students were suspicious.

“Everyone thought I was an undercover cop,” he said.

Weber is 6 feet 6 and 310 pounds, but it wasn’t his size that elicited stares. It was the color of his skin.

Weber is one of only seven white students in a student body of almost 2,000. And he is the lone Caucasian playing football for a school where African Americans are 62% of the student population.

His experiences at Dorsey have given him a unique perspective on race relations and the power of sports as a unifying force.

Last year, Weber moved from Mammoth, where he lived with his older brother, to his parents’ home less than two miles from Staples Center.

“The reason Nathaniel went to Dorsey was he wanted to play serious football,” his mother, Heather, said.

Weber enrolled during the summer and worked out with the team to see how he’d fit in.

“I was there for two hours a day meeting people,” Weber said. “Everyone was seeing I wasn’t giving up and I wasn’t racist.”

Weber started every game at center last season.

“He came right in and had no problems,” said Paul Knox, Dorsey’s coach. “He developed relationships with guys on the team during the summer and by the time school started a lot of people knew him and he was an integral part of the school community.”

Weber is the youngest of four brothers, three of whom attended Los Angeles Fairfax High. His father, William, is a chemistry professor at USC. His mother teaches molecular biology at Los Angeles City College.

The family home was once owned by Hattie McDaniel, the first African American actress to win an Academy Award for her role as a maid in “Gone With the Wind.” The neighborhood, while ethnically diverse, pales in comparison to the visitors who frequently stop by the house.

Besides Nathaniel’s friends from the football team dropping in to swim in the pool, his parents hold gatherings for visiting scholars and teachers. It’s not uncommon for acquaintances from India, Taiwan, China or Russia to be sitting at the dinner table.

“Our house is filled with people from around the world,” Heather said.

Living in the city doesn’t frighten the Webers--it empowers them. William rides his bicycle to USC each day, traveling 31/2 miles over streets his colleagues say they wish they didn’t have to drive through.

During the 1992 riots, Heather remembers filling up her car at a local gas station and being the only one not holding an automatic weapon. From their home, they could see fires burning.

But they feel secure and safe with their two cats and three dogs, led by Yogi, a black Karelian bear dog.

“When you come to the gate, his bark changes from a warning bark to, ‘OK, step in here if you dare,”’ Heather said.

They live in the Los Angeles High district but Nathaniel wanted to test himself in football at Dorsey, which won City Championships under Knox in 1989, ’91 and ’95. Being among the few white students on campus was never an issue.

“I was concerned whether there was any gang stuff,” Heather said.

During the 1990s, Dorsey’s reputation took a beating because of shooting incidents near its Southwest Los Angeles campus.

In 1991, Banning refused to play the Dons in a football game at Jackie Robinson Stadium, fearing violence in the aftermath of two gang-related shootings near the stadium.

There were shooting incidents near campus in ’93 and ’96. In the summer of ‘99, two Dorsey graduates were wounded in front of the school in a gang-related attack.

“There’s never been a big problem on campus, so the misperception of the school was there were gangs and shootings,” Knox said. “That was never really the truth. We have a safe environment and students can come, learn and be successful.”

Football clearly helped ease the transition for Weber. Once he earned his teammates’ respect in practice, he was accepted as just another Dons player.

“He just fit in,” lineman David Barker said. “He didn’t need to change his ways. He was himself. He gets along with everyone. He’s cool, really cool.”

Weber is into cars. Scouring junkyards for spare parts, he built a 1969 International Scout from scratch.. He learned to snowboard in Mammoth, earning the nickname “Avalanche” from his brothers.

He believes most of his Dorsey classmates see him as “just another student,” but he acknowledges that there are some teachers and teammates who are uncomfortable around him.

“There’s like four, five people on the team who look at me a different way,” he said. “I don’t know why. I don’t touch the issue.”

Weber’s education involves more than just reading text books or writing essays. He’s learning about the lives of his African American friends and the problems they encounter in a society that’s still battling racial stereotypes from past centuries.

And he has seen racial profiling up close.

“I’m driving and a cop won’t pull me over because I’m white,” he said. “My friend who’s doing the same thing I’m doing got pulled over. If he has music up loud, he’ll get pulled over and I won’t.”

Asked how his life has changed going to Dorsey, Weber said, “I think it’s going to make me more aware of what’s going on and not to judge people. I learned it’s no different than anywhere else and you have to treat people with respect.”

Weber has a 3.1 grade-point average in Dorsey’s math-science magnet and has committed to accepting a scholarship offer from Michigan State.

He shrugs off the significance of his place on the Dorsey football team, but make no mistake--it’s a big deal. Ten or 20 years ago, he probably wouldn’t have chosen Dorsey because of racial tensions and security concerns.

Times have changed and minds are changing.

“It shows people are accepting and it doesn’t really matter your race, color or ethnicity,” Knox said. “If you’re a good person, they’ll accept you.”

*

Eric Sondheimer can be reached at [email protected]

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.